CAA: Interview with Tito Rivas, Fonoteca Nacional

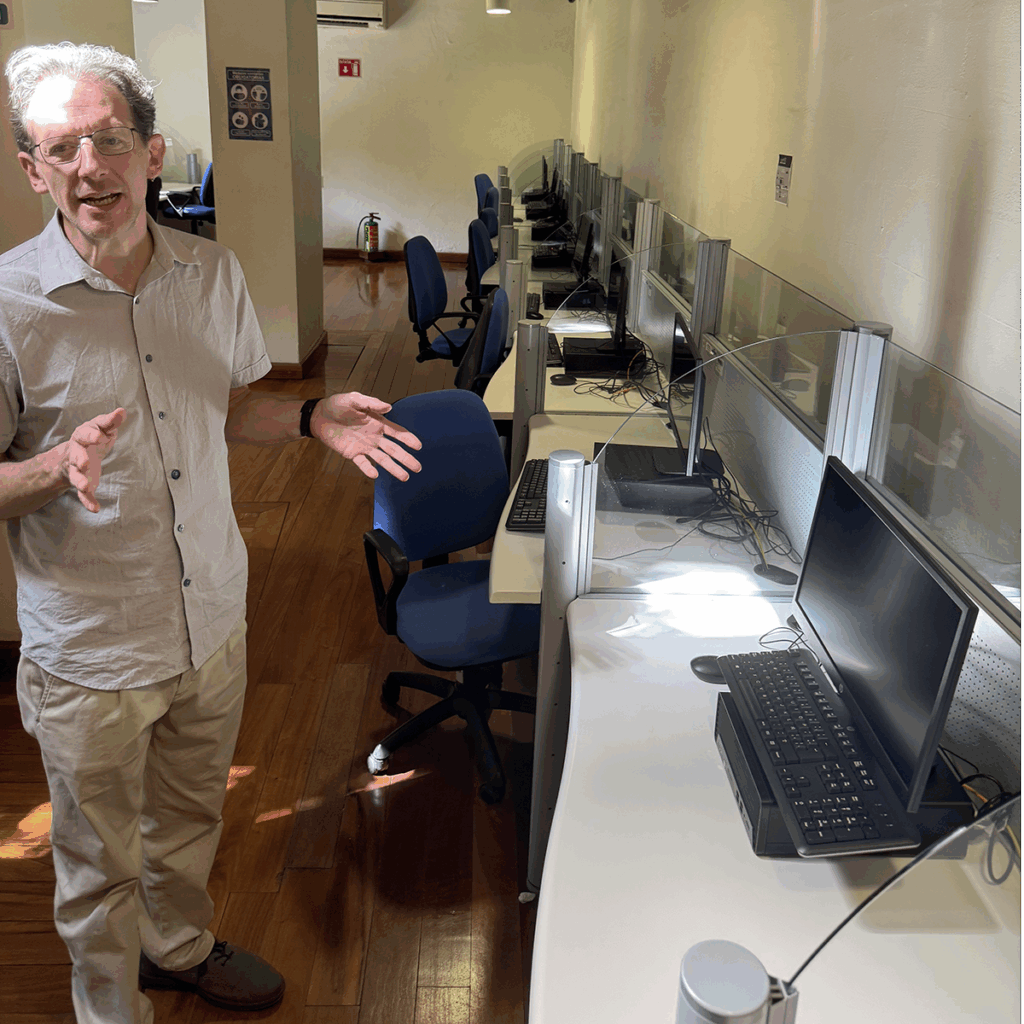

As part of an initiative to expand public access to the Creative Audio Archive (CAA), ESS is conducting a series of interviews with peers in the field. In the first interview of that series, CAA Manager James Wetzel spoke with Fonoteca Nacional’s general director Tito Rivas about the challenges of turning archives into spaces for listening.

This transcript version of the interview has been adapted from the audio recording. It has been paraphrased and edited for readability, and the final version was approved by the speakers.

The original interview was conducted August 6, 2025.

Listen to the full interview here:

James Wetzel (Experimental Sound Studio): To start, could you share a little more about your work there—your role, who you are, and more generally about Fonoteca Nacional and the work you’re doing with the archives?

Tito Rivas (Fonoteca Nacional): My name is Francisco, though most people know me as Tito. I’m the General Director of Fonoteca Nacional of Mexico. Fonoteca is a government institution that serves as the national sound archive. Our mission is to identify, collect, preserve, and disseminate what we call Mexico’s national sound heritage.

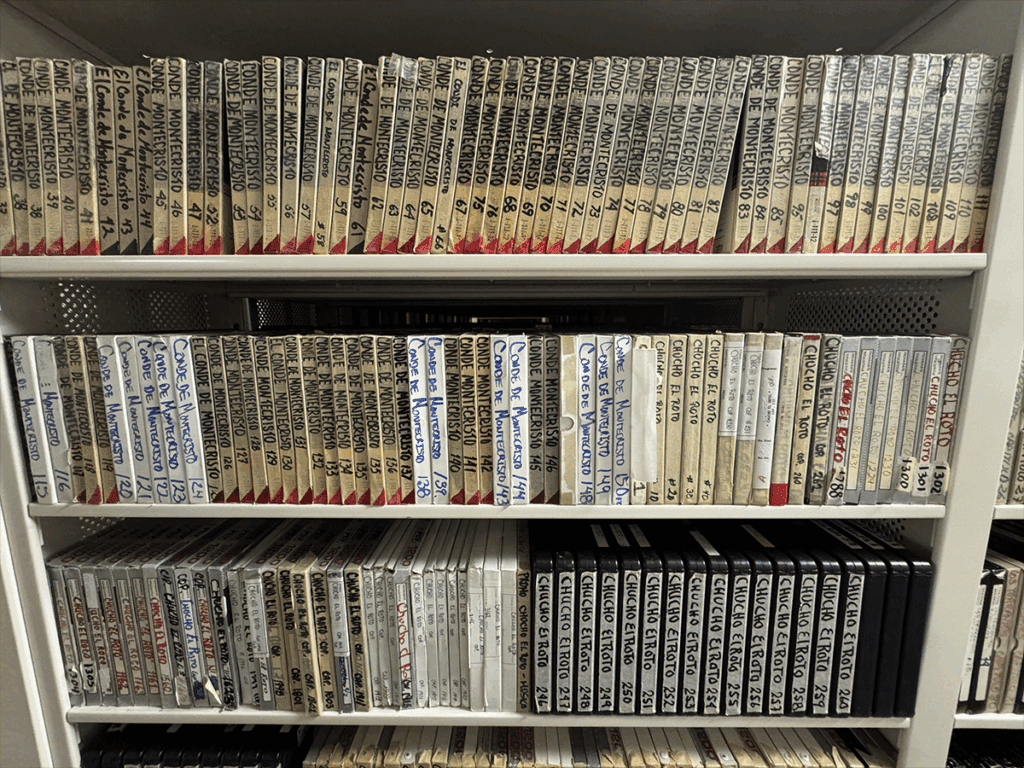

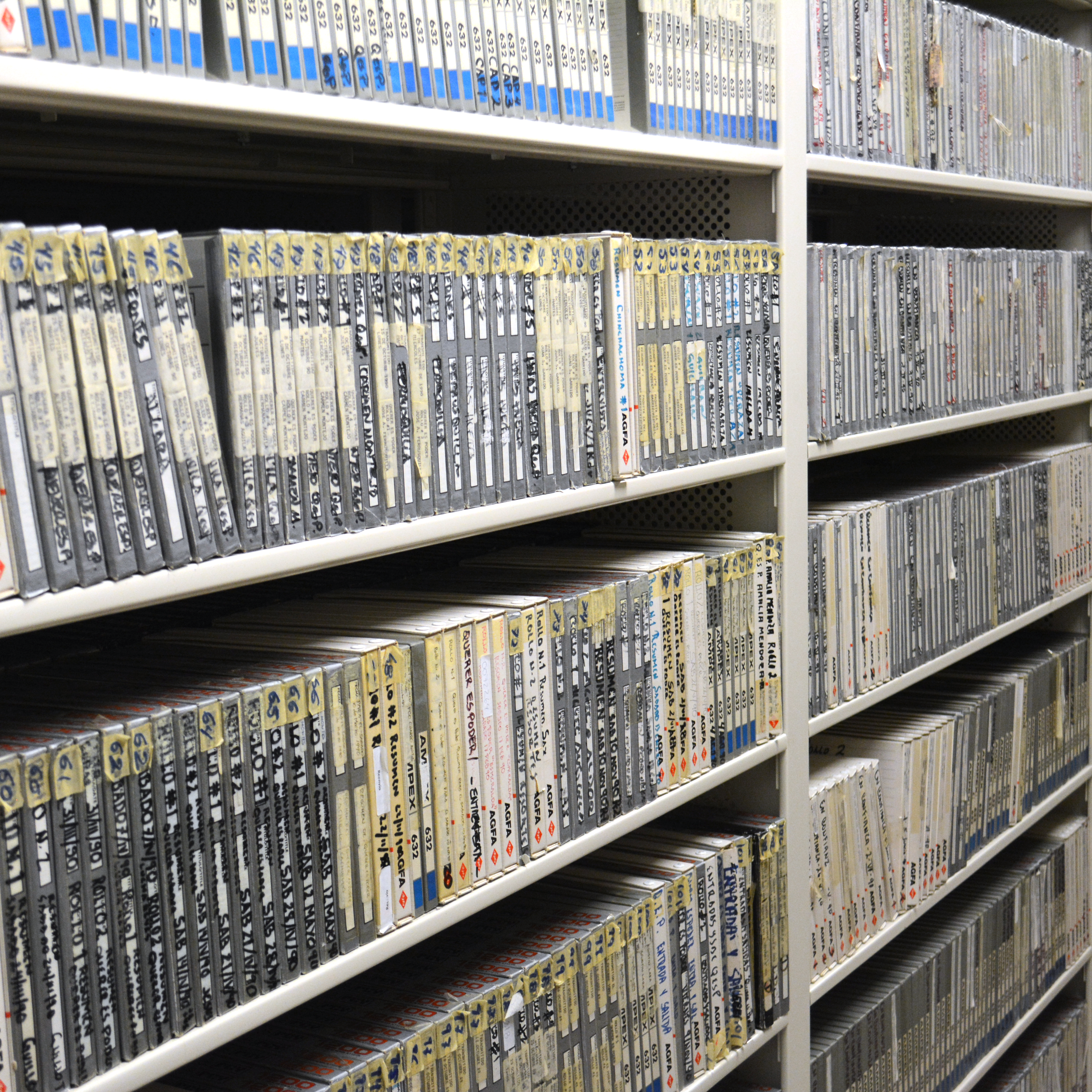

That phrase can be complex, and we can discuss later what exactly it means. But in general we’re talking about audio recordings made since the invention of sound recording technologies that have cultural value. The institution has existed for about 15 years, and in this first stage most of our work has focused on recovering and preserving analog formats.

James: The scale is fairly large. I know you have a big team and a lot of people working on these materials. In terms of volume—how many recordings have been digitized, how many items are you processing, and what does the library look like?

Tito: When Fonoteca Nacional was conceived there wasn’t anything like it here. But there were sound collections in private and public organizations, each preserving recordings in their own way. There were no shared guidelines for cataloging, organization, or long-term preservation.

When you deal with such large volumes, it’s essential to have clear criteria. So one of our first tasks was to identify those existing archives and bring them together.

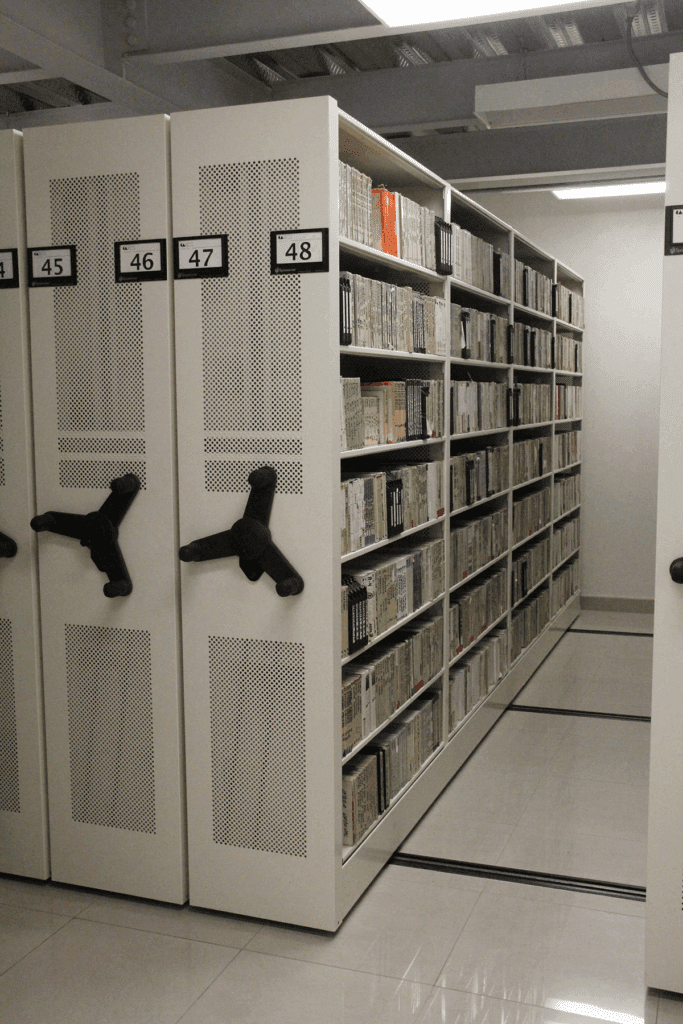

At the beginning we compiled about 220,000 sound documents. That was enormous from day one. It wasn’t easy: first identifying the collections, then convincing organizations it was safe to bring them here. At the same time we had to build dedicated infrastructure—storage rooms with controlled temperature and humidity, fire protection, everything required for preservation.

The project began in 2004 and culminated in the opening of Fonoteca Nacional in 2008. Four years might seem fast considering all it required: identifying collections, creating workflows (which we’ll talk about later), and constructing the building.

From that start of 220,000 recordings, the archive has grown steadily over 15 years. Today we hold about 655,000 sound documents. Alongside that growth we’ve developed workflows and trained staff to handle the work rigorously and scientifically, always with the goal of preservation.

James: I’m interested in the methods you created to manage such a large collection. What worked, what didn’t? When you spent those four years building Fonoteca Nacional, who did you look to for models? Was it library science methods, trial and error, or a mix?

Tito: Looking back, I feel it was like planting a seed. The first step was to create the agenda, to make people understand this was important. Without that, we would never have secured the financial resources such a big task required.

Credit belongs to the founder of this institution, Dr. Lydia Camacho, who led the project. I was proud to be part of her team helping to conceptualize it, but she was the one with the vision and the strength to realize it.

Those early years were about creating the intellectual framework in which a national sound archive made sense. The International Seminars on Sound Archives, which we began hosting then, were crucial. We invited specialists from around the world to share their experience, which we analyzed carefully in order to shape the Mexican national sound archive.

We received a lot of knowledge from the Swiss National Sound Archives, which served as a model—even down to the word “phonotheque.” We also learned from the Phonogrammarchiv in Vienna, and from German radio archives. We joined IASA, the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives, which connects the major archives worldwide.

At those seminars we welcomed people from the BBC, the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian, and archives in Australia. The Phonogrammarchiv in Vienna opened in 1898, so they had more than a century of experience. All that knowledge became the foundation of Fonoteca Nacional.

At the same time, we contributed our own approach. We conceived Fonoteca not only as an archive but as a cultural institution that would activate listening through public programs: listening sessions, concerts, artist collaborations. That broader vision helped the archive succeed in connecting with society.

James: That’s wonderful to hear. We’ve talked about the scientific approach—cataloging, intake, digitization—but also the importance of activating collections so they don’t just gather dust. That’s something we try to do at ESS as well: treating the archive as living, not static. When I visited, I was struck by your listening stations and the sound map, which invite public participation. Did you visit archives like the Swiss Phonotheque and the Vienna Phonogrammarchiv, or did their representatives come to you?

Tito: Both. Our staff traveled there, and their experts came here. It was an intense period of knowledge exchange. Together we studied possibilities, designed workflows, and decided how the archive would function.

For example, choosing how to organize the collection, how to digitize, even which software to use. Based on their advice we adopted NOA Solutions, which at the time was a leading audio archive management system.

From the very beginning we faced the challenge of managing huge quantities of material—more than 200,000 recordings. That required a “massive solution,” a digital audio workflow on a large scale.

There was also a sense of urgency. In the 1980s UNESCO warned that audiovisual materials faced two threats: degradation of physical carriers, and technological obsolescence as playback machines disappeared. By 2004 we were already seeing that.

So the first priority of Fonoteca was urgent collection and mass digitization, to win the battle against time. At that point it was said magnetic tapes had about 25 years left. My own experience is that with proper temperature and humidity you can extend their lifetime, which gives you more time to design better strategies.

In the beginning we prioritized quantity, digitizing massively. That was necessary. But later we realized that quantity sometimes compromises quality. So we learned to pause and ask: is this the best way? Because once you start, it’s difficult to go back. With such large volumes you can’t simply decide to redo years of work.

My conclusion is that these processes must be thought through very carefully. They will always involve some trial and error, but the stakes are high.

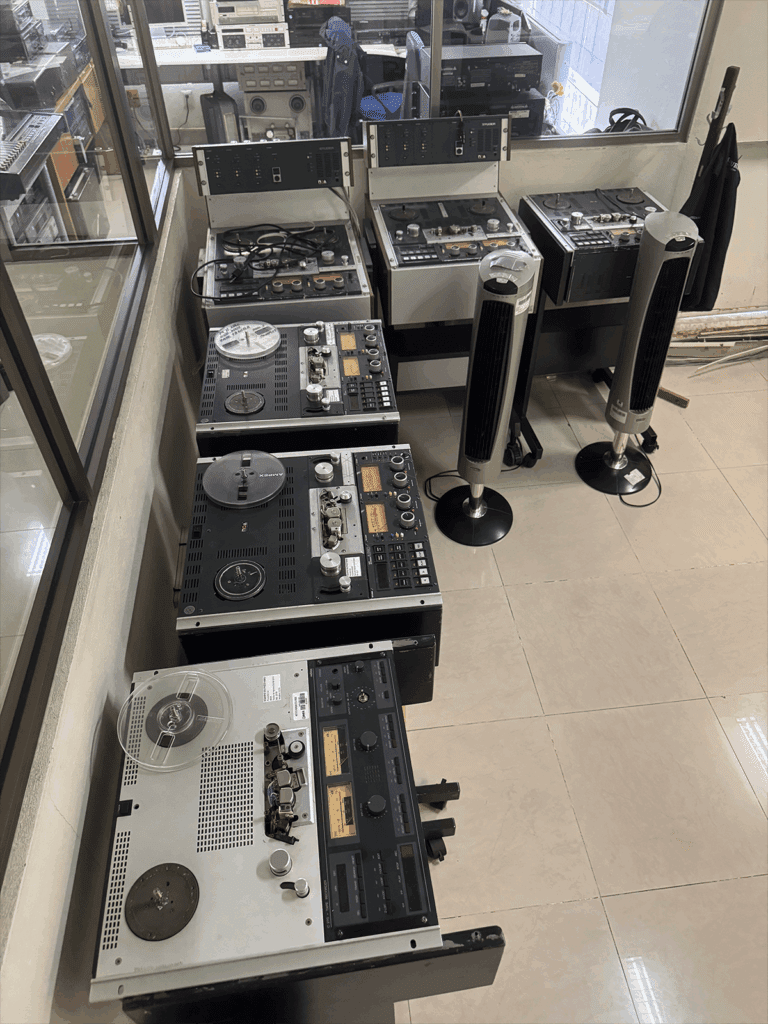

James: We face similar challenges. Collections arrive in all conditions—sometimes they’re already damaged beyond saving. And of course we depend on equipment. When I visited I saw your shelves of decks, different brands, some working, some not. You mentioned that sometimes listening to the machine itself is as important as listening to the transfer. How do you handle maintenance, and how do you acquire equipment?

Tito: That is one of the biggest challenges in recovering an analog archive. You need the machines, but also the knowledge of how they work.

I enjoy this part because it connects with what is now called “media archaeology.” There’s the technical side: how the heads read the tape, how reels move, playback speed. But there’s also the cultural side: each machine was built in a context, for specific listening practices.

When we transfer material to digital, we’re not just moving between formats—we’re moving between technological and cultural systems. Jonathan Sterne, a theorist who sadly passed away recently, wrote about how sound technologies are embedded in networks of knowledge and practice. Machines are not just artifacts; they’re mirrors of the culture that produced them.

So preserving machines is also part of preserving cultural heritage. They are museological objects that let us study the sonic era.

Practically speaking, we maintain them with the help of a specialized engineer. Many machines come from donations. People often don’t want to keep large, obsolete equipment, and when they hear about our work, some donate instead of selling.

James: That happens with us too. Sometimes you just use what works, and the artifact you get is what you get. You also mentioned the importance of knowing how media was originally recorded and using a similar device to digitize it. Is that crucial for you, and do you want listeners to know not just what the sound is, but how it was recorded?

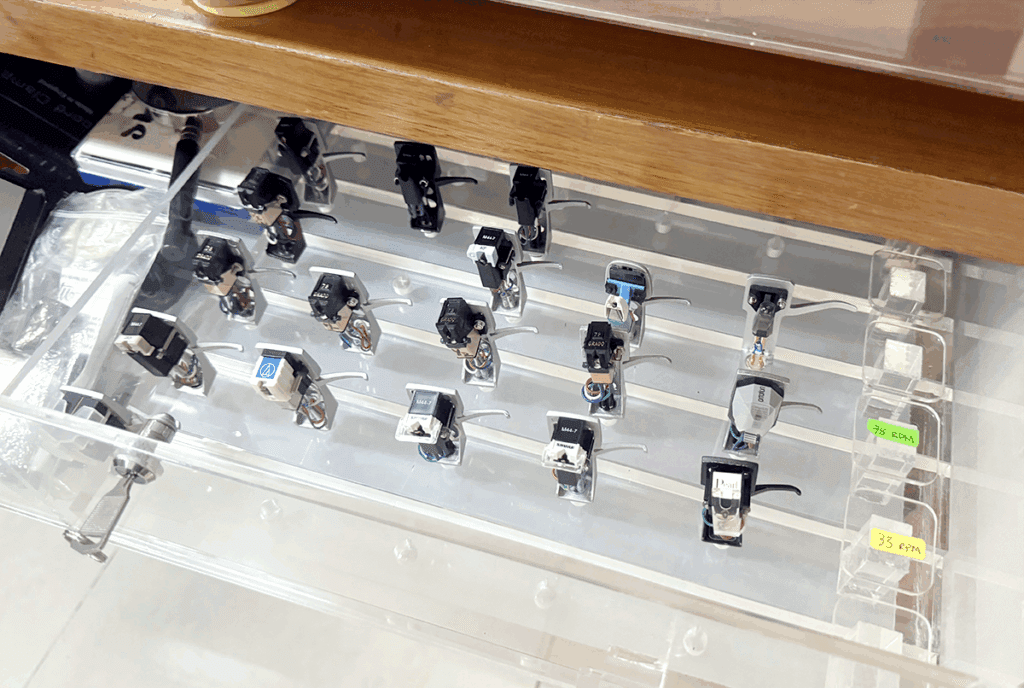

Tito: Yes, especially with grooved discs. For every disc we digitize, we analyze the period, the company, and the recording techniques they used. Sometimes all you have is a serial number, but that can tell you the year and method if you consult old catalogs from Columbia, RCA Victor, Edison, and others.

We maintain a collection of styli. The team studies each disc and selects the correct stylus. Choosing the wrong one can damage both disc and stylus.

This work is more time-consuming, but it produces better results. In the early years we focused mainly on reel-to-reel magnetic tape. We still do, but we now devote more time to careful transfers of discs. It takes longer, but the quality is higher and the process itself is satisfying in a different way.

James: It’s more physical than tape—you’re literally working with grooves and vibrations.

Shifting now to the public side: one of the goals of this series is to discuss ways of activating personal stories that come through recordings. How do you move from a digitized tape on a shelf to something the public can actually hear?

Tito: The physical, material side of the archive is one part. The other is listening. If you create a sound archive without thinking about how it will be listened to, you’re missing the point. Making the archive audible is the hardest part, but it’s also the main purpose.

In the beginning we assumed it would be like a cinémathèque: they screen films, so we would simply program listening sessions. But almost nobody came.

We realized listening is not a shared cultural practice in the same way. People go to concerts, yes, but listening together to recordings is unusual. At home, listening has shifted from gathering around one radio to individualized headphone listening. So we had to produce listening. One strategy was to invite people not only to play recordings, but to share why they chose them. That simple change transformed the experience into a communicative act.

We call these listening sessions. Someone guides you through a path of recordings, like a tour. We invite musicians, writers, artists, sociologists, scholars—different voices. Now we host them weekly, and people respond enthusiastically. They leave smiling.

James: So they’re like listening tour guides. Do they select material from Fonoteca, or bring outside recordings, or research a specific collection?

Tito: Both. We encourage them to start with our archive, because every time someone listens here it creates knowledge—even discoveries. No one, not even me as director, knows the whole archive. It’s too large.

We also welcome outside material when it can be incorporated. And we record the sessions themselves, which then become part of the archive. In the future, someone researching an artist might find not only the artist’s recordings but also a listening session where someone contextualized them.

So the object—each recording—moves through stages: cleaning, preservation, cataloging, and listening. Each stage adds layers of knowledge. You might learn the recording technique, or that a singer tried a genre for the first time, or that two artists were connected personally. All of these details expand the “aura” of the object.

James: That’s like sonic archaeology. There’s also urgency: people with firsthand knowledge are aging. Without context, recordings lose part of their value. Beyond in-person sessions, do you support online conversations—allowing people to comment, add information, or submit their own materials?

Tito: Well, yeah. I mean, up to now we’ve been developing what we felt was the most efficient strategy to communicate the archive, mainly through digital and online platforms. I should say from the start that, unfortunately, we can’t share our whole catalog online because of copyright issues. And since we’re a public and governmental institution, we can’t go against federal copyright law.

What we do instead is create alternative strategies to make the archive available online. We have a website where we share material, and during this time we’ve developed a lot of content that highlights the archive and the discoveries that come out of our work. For example, someone might come across an old tape that just has a number on it. Out of curiosity, they play it back and discover a recording no one knew was there. We have a team dedicated to capturing and identifying these kinds of discoveries. But it’s not just about discovery. We also have a research team made up of specialists in different areas. We call them “researchers,” but they’re also creators in their own right. One might specialize in concert music, another in traditional Mexican music, another in radio programs, literature, soundscapes, or field recordings. Whatever the subject, we have someone on it. These people are constantly listening, taking notes, and making connections. They’re doing curatorial work, making selections, and then collaborating with another team to transform their research into content. That could be microsites devoted to an artist, a genre, a period, or a type of sound expression.

We also have a podcast, with about two episodes a month, where we go deeper into certain topics. And we interact a lot with people through social media. We’re constantly creating different content. For instance, we have a series called “Stories from the Archive,” or another based on the “Mexican Sound Map” you mentioned. In those, we share recordings with a short script of the audio and some text that’s interesting enough for someone scrolling on their feed to stop and press play.

We’ve been pretty successful with this recently. Some posts get more attention than others, but the important thing is to keep putting things out there. It’s like fishing: you cast your line, and sometimes you catch something, sometimes you don’t, but you have to keep doing it. That’s the strategy we use to connect with the community.

And the nice thing is that this creates interaction. Sometimes people write to say, “You mentioned this, but I have recordings you might be interested in.” Other times they correct us—“No, that didn’t happen in that year.” Even when it comes from haters, we see it as positive. If you don’t have haters, it’s not social media. What matters is that we’re creating conversation around the archive.

We also keep in mind that we’re a public institution. Our funding comes from taxes, so we have a responsibility to give something back to society. That means we can’t just follow our personal tastes. We have to keep the conversation as wide and open as possible. Of course, it will always be subjective, and if another team did this work they’d do it differently. But as an institution, we try to keep in mind that this is social work too, and that our role is to open up the conversation as much as we can.

About Tito Rivas

Francisco J. Rivas Mesa has a degree in Audiovisual Communication from the Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana and in Philosophy from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). He is a candidate for a Doctorate in Musical Technologies from the Faculty of Music of UNAM. He has a Diploma in Executive Training for Cultural and Museum Leaders (ILM, Universidad Iberoamericana). His work has focused on experimentation with sound, visual and performative media as a creator, researcher and cultural manager. He has also been interested in strategies to produce social and ethical access to archives and their reuse for educational and cultural purposes. He has been a professor of subjects on sound and audiovisual creation in academic institutions and as a creator and curator his work has been presented and exhibited in various national and international venues and festivals. He has also published specialized articles on sound phenomenology and the archeology of listening. He is a member of the Sound and Listening Studies Network (RESEmx) and the Scientific Committee of the Mexico Acoustic Ecology Network (REAmx). He was part of the team that inaugurated Mexico’s National Sound Archive in 2008 as head of the Sound Research and Experimentation department and as Deputy Director of Sound Promotion and Dissemination. He was curator of the Espacio Sonoro de Casa del Lago (UNAM) and director of the Ex Teresa Arte Actual museum of INBAL. He is currently general director of the National Sound Archive of Mexico and president of the Ibermemoria Sonora, Photographic and Audiovisual Program.

Francisco J. Rivas Mesa has a degree in Audiovisual Communication from the Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana and in Philosophy from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). He is a candidate for a Doctorate in Musical Technologies from the Faculty of Music of UNAM. He has a Diploma in Executive Training for Cultural and Museum Leaders (ILM, Universidad Iberoamericana). His work has focused on experimentation with sound, visual and performative media as a creator, researcher and cultural manager. He has also been interested in strategies to produce social and ethical access to archives and their reuse for educational and cultural purposes. He has been a professor of subjects on sound and audiovisual creation in academic institutions and as a creator and curator his work has been presented and exhibited in various national and international venues and festivals. He has also published specialized articles on sound phenomenology and the archeology of listening. He is a member of the Sound and Listening Studies Network (RESEmx) and the Scientific Committee of the Mexico Acoustic Ecology Network (REAmx). He was part of the team that inaugurated Mexico’s National Sound Archive in 2008 as head of the Sound Research and Experimentation department and as Deputy Director of Sound Promotion and Dissemination. He was curator of the Espacio Sonoro de Casa del Lago (UNAM) and director of the Ex Teresa Arte Actual museum of INBAL. He is currently general director of the National Sound Archive of Mexico and president of the Ibermemoria Sonora, Photographic and Audiovisual Program.